The human thyroid gland is a small organ a few centimetres in size, the two wings of which mould to the trachea in the area of the larynx. The characteristic name originates from the physicians of ancient Greece who recognised a shield (thyreoides = shield-like) in this organ that protects the larynx. Today, the thyroid is usually referred to as “butterfly-shaped” because its symmetrical wings are reminiscent of the well-known insect.

Function & tasks: what does the thyroid gland do?

The main task of the thyroid gland is producing the hormones triiodothyronine, thyroxine and calcitonin. The first two hormones act as the main regulators of the human energy balance, while calcitonin plays a role in bone health. If thyroid function disorders occur, the consequences affect the entire body, as well as our well-being.

Thyroid hormones: energy & rgeneration

The thyroid gland fulfils its function in human metabolism via the hormones triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4). These two signalling agents interact with our mitochondria to boost energy production. As a result, metabolism increases to a level that allows physical and mental exertion. This stimulates fat burning and carbohydrates are made available for daily consumption. Thermogenesis, i.e. the body's own heat formation, is stimulated and core temperature increases. The pulse accelerates and calorie consumption is increased. The energy is there, the body is “revved up” and ready to go. In addition, cells now have enough energy to divide. This renews the skin, wounds heal, muscle repairs itself and hair grows back. In children, this energy is essential for normal development, as cells have to divide particularly often as they grow. All of these tasks are completed by hormones T3 and T4. The third hormone produced by the thyroid gland, calcitonin, inhibits the release of calcium from the bones, thus supporting bone health.

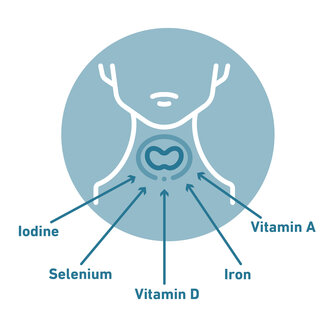

Micronutrients that support thyroid function

Iodine and selenium are essential for thyroid function

In order to form the hormones T3 and T4, the thyroid gland only needs two ingredients: theamino acid tyrosine and the trace element iodine. While tyrosine is not essential, i.e. it can be formed by the body itself, iodine must be supplied via food. Regular intake is important because the body loses about 100 μg of iodine per day via urine. This is also how we calculate the daily requirement: between 150-200 μg iodine should be ingested every day to compensate for losses. If too little of the trace element is fed in, the body initially reacts by reducing excretion. An iodine deficiency can therefore be detected in the urine – if the body excretes less than 100 μg iodine per day, this indicates suboptimal care. If the important trace element is missing in the long term, the levels of T3 and T4 are reduced, because there is insufficient building material. In response, the body releases the so-called “thyroid stimulating hormone” (TSH), which stimulates the thyroid to increase activity. This allows the organ to better recycle used T3 and T4 in order to really use every last bit of iodine. In the short and medium term, enough T3 and T4 can be made available even if iodine intake is reduced. In the long term, however, long-term stimulation by TSH causes increased cell division in thyroid tissue. In the attempt to meet the increased hormone requirement, the organ can thus grow beyond its normal size. A bump then forms in the larynx area – the so-called goitre. If you want to compensate for the iodine deficiency, caution is advised: if too much iodine is absorbed too quickly, the enlarged thyroid switches to turbo mode and produces excessive amounts of T3 and T4. However, if the iodine deficiency is remedied patiently, the thyroid often shrinks back to its original size and its function normalises.

Selenium is also essential for the function of the thyroid gland. The trace element is part of the conversion process from T4 to T3. This step is particularly important in the hormone balance of the thyroid gland, since T3 is almost four times as active as T4. Selenium is also essential for neutralising free radicals in the thyroid gland. A selenium deficiency can slow this process, increasing cell damage in thyroid tissue. The resulting chronic inflammatory conditions can lead to an autoimmune disease. In addition to iodine supply, selenium status is also an important criterion for a healthy thyroid gland.

Other micronutrients

Other important micronutrients that can support the function of the thyroid are iron and vitamins A and vitamin D.